Introduction

By Diana Young, Director UQ Anthropology Museum

Snakes are a threat to humans especially during Australian Summers. Following recent incidents of King Brown and red bellied black snakes biting humans, Queenslanders are being told by media that thirsty snakes could come into Queensland’s suburbs, forced there by the drought and the forecast el Nino weather pattern. Snake bite incidents are becoming common place. The agency of snakes and their power to disrupt the order of things and effect new circumstances is the subject of all the objects in this small collection generated Summer show in the UQ Anthropology Museum gallery.

Although the things in this exhibition are classified inside the Museum’s catalogue system according to the type of object that they are – ‘shield’, ‘throwing stick’, ‘spear thrower’ -they have something fundamental in common. Each work in different ways images pairs or groups of snakes.

The works were created by Indigenous makers living and working in central and Western Australia and Queensland. There is a spiritual link between snakes and humans for the artists. In many ways these images are the precursors of paintings on canvas. Morton explores the link between support and design in his catalogue essay. Morton is uneasy about the lack of information attached to many of the objects; what are they ‘really’? Are these images fundamental to the objects or subtractable from them?

This lack of background information is one of the challenges of the so-called ethnographic museum. Yes in some ways this lack gives the objects more possibilities, a spirit of open endedness and a first step towards the possibility for the objects on display to make new connections with each other - and with you the visitor - and bring themselves into the present. Offering these things a chance in the light are the best terms currently on offer.

The idea that once an object enters a Museum it ceases to have any new social life and simply lives out a twilight after life of suspended animation is pervasive but is also being challenged. Museum objects have relationships among themselves. The majority of these things have spent longer in the collection than ever they did out in the world. And their biographies have holes in them. If the collectors are still alive what they noted down at the time is all that lasts. We forget these details. For example one donor bought this boomerang when he was stationed at Woomera in the 1960s. He took it with him when he went home with it to the UK and, returning on holiday in 2010, brought the work here to UQ wanting it to be home in Australia. He can’t recall where he bought it.

His story with all its omissions tells us about power relations not only between Britain and Australia in the 1960s but about the man who made the throwing stick (boomerang) to sell. As to his story there is no recorded trace except for the trace of his hands on the object, his shaping of it and careful treatment of its snake skinned surfaces that give way to polished wood where the snake bodies are.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to John Morton

Objects, Images and Serpents

John Morton, Humanities and Social Sciences

La Trobe University

The objects and images in this gallery come from across a large swathe of Aboriginal Australia – from the Kimberley, Wadeye (Port Keats) and Mornington Island in the north to Brisbane and the central Australian desert in the south, although the original location of some objects is unknown.

The objects and images have been brought together because they contain, or appear to contain, snake motifs. But is there anything these objects and images have in common beyond some apparent connection with a serpentine form? After all, the imagery is highly varied. Some snakes embrace; some lie side by side or face to face; others seem to coil, or lie alone, or follow each other in procession. Most are accompanied by other designs, some clearly figurative, others seemingly abstract. In one case, the object actually is the image, since although it is a throwing stick, it is also a serpentine sculpture. Are all these configurations variations on a theme? And if so, what do they tell us about the imagination of Aboriginal Australians? Or is the association of these objects arbitrary, perhaps based on not much more than a curator’s desire for an idea to drive an exhibition?

Given how little is known about the objects as a whole, these are difficult questions; so the safest place to start is with those objects that have the best provenance – the acrylic paintings by Barbara Nipper Tjakatu and Niningka Lewis, and the silkscreen prints by Jimmy Pike and Ron Hurley.

The Nipper Tjakatu painting, from Mutitjulu, has two titles: ‘Kuniya Tjukurpa’ or ‘Python Law’, and ‘Kuniya and Wati Kuniya’ or ‘Python Woman and Man’. In Western Desert languages, which are spoken across much of the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia, ‘tjukurpa’ is used refers to a number of related concepts to do with cultural rules set down at the beginning of time by ancestral beings – hence the translation as ‘Law’. But the rules are inherited by the living through origin myths and associated symbolic forms, including song, drama and plastic arts. Hence, ‘tjukurpa’ can also be translated as ‘story’ – or, as it is often called in Aboriginal English, ‘Dreaming’. Ancestral beings are characteristically ‘totemic’, meaning that they are not only human, but also ‘more-than-human’ and able to exhibit the characteristics of non-human species. The ancestors depicted by Barbara Nipper Tjakatu are ‘kuniya’ – non-venomous constrictors or pythons – and the story is associated with events at Uluru (Ayers Rock), where a female python hid her eggs and avenged the spearing of her nephew by members of another snake group, the venomous ‘liru’. The two python protagonists and the female’s eggs are clearly shown in the painting against the backdrop of a varied landscape symbolised by blue, brown and green stippling.

Lewis’s painting is titled ‘Malara’, which is the name of a sacred site and Aboriginal homeland in north-western South Australia. The place is linked by story to Uluru and has associations with the snake protagonists involved in Barbara Nipper Tjakatu’s painting, since Malara is a home of Wati Liru – the poisonous snake men who killed python woman’s nephew at Uluru. But Malara is also connected to another snake, Wanampi, an aquatic creature that dwells in waterholes and is often identified as a ‘rainbow serpent’, a mythical python-like creature found throughout Aboriginal Australia, albeit in a plethora of forms. Without further exegesis, it is not possible to say for certain that Lewis’s painting is a rainbow serpent story, but the arch-like patterns in the imagery seem to suggest this, as do the doubling and symmetry of the snakes. Wanampi exists in a twofold aspect, male and female, and this is mirrored in the phenomenon of the double rainbow, whose parallel arches oppose each other by reversal in the order of their colour spectra.

Jimmy Pike’s silkscreen print is titled ‘Kalpurtu Watersnakes II’, thus indicating its likely affinity with Lewis’s painting. Although not explicitly said to be associated with rainbows, kalpurtu snakes act in the same way by bringing about storms and the torrential downpours that intermittently reinvigorate the desert landscape. Pike created a number of images of kalpurtu and their home at Japingka, a waterhole in the Great Sandy Desert. In one a kalpurtu is depicted as a multi-coloured serpent with four legs, a bearded human face, and what appears to be a ceremonial headdress. In others, the kalpurtu is said to be the guardian of Japingka Waterhole or the master of its essential element, water. All this reflects both the ecological importance of the place and its spiritual significance as a homeland to which Pike had a duty of care. Whether or not the two snakes in the print are the serpent in its male and female aspects is not clear, but it is certainly the case that this symbolic theme has been reported from areas close to Pike’s country.

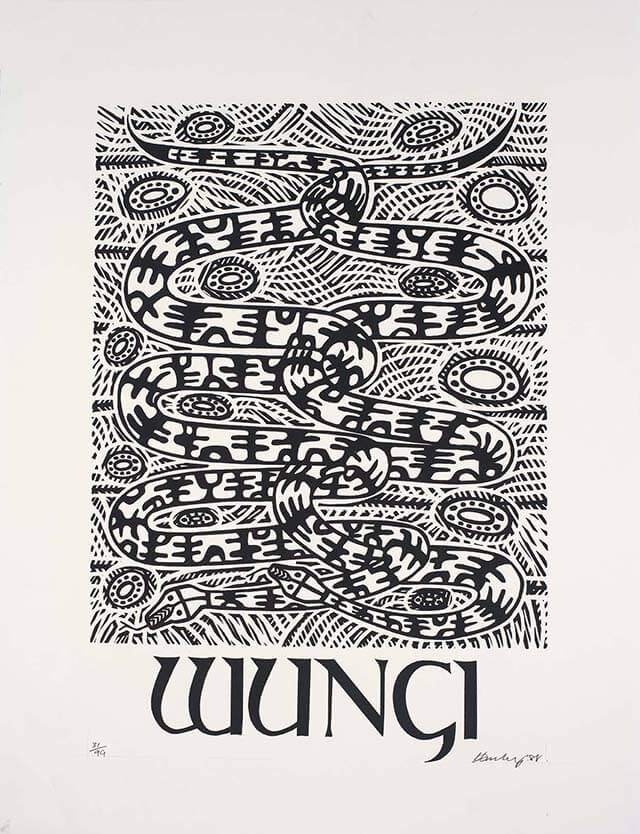

Hurley’s print contains echoes of the other three works, although it is not from a desert region. Hurley grew up in Brisbane and was associated through his parents with countries to the south of Brisbane and north of Bundaberg. The print is called ‘Wungi’, which means ‘snake’ in the Goreng Goreng language, although the work specifically depicts a dimorphic pair of mating carpet pythons and their eggs lying about on grassy ground, and alludes to the ecological importance of python breeding. Unlike the other three works, Hurley’s print has no narrow local reference. It is not a site-based story, but rather one by which Hurley draws attention to the whole language group area of his mother and to Goreng Goreng people’s traditional connection to local ecology. Nevertheless, the formal parallel with Pike’s print is striking and invites the viewer to think about comparison. One possible connection lies in the fact that Goreng Goreng people are traditional owners of country where the population was once divided into totemic clans, each associated with one of the two halves of society (‘moieties’) whose members had to intermarry. In some cases, opposed, intermarrying totems were not distinguished by species, but by colour or gender within species. Although no direct evidence bears on the question, it is quite possible that Hurley incorporated this mode of opposition into his breeding carpet snake pair, since the male snake is said to be gold, while the female is reckoned as red.

There is very little information about the other ten objects in the collection. The reproduction and eggs motif seems to reappear on one of the painted shields, although, since there is no information about this object, we cannot even be sure that the eggs are eggs, let alone those of a snake or snake pair – this in spite of the suggestive meandering shapes along the outer edges of the shield. Dimorphism can again be seen in the pokerwork painted snakes on the throwing stick from Mornington Island, in Queensland’s Gulf Country, since only one snake has an elongated, blackened neck; but the significance of this difference remains a mystery. Yet more intriguing are the entwined snakes depicted on the intricately carved spear-thrower, which, apart from having differently marked heads, are accompanied on one side by carvings of a water buffalo head, a horse head and three suits from a playing cards deck, and on the other side by a star design, a stool, two boomerangs and two potted plants. The buffalo head almost certainly means that the spear-thrower is from the Top End of the Northern Territory, while other motifs are perhaps suggestive of life on a pastoral station. Are the twin snakes mating? Or are they perhaps fighting? We do not know; but the carvings overall do suggest a historical narrative in which the snakes must have played a part.

A narrative structure also seems readily apparent on the shield from Wadeye, since the object has a number of panels on each side with classical Aboriginal motifs indicative of location and travel, although several contain realistic images of snakes – two pairs on a rear panel and groups of three and five on panels at the front. The many zig-zag designs on the front panels of the shield look like snake tracks, while the panel with five snakes clearly shows a human character in ceremonial garb being bitten on the genitals by one of the snakes. It should be remembered when looking at this object that shields are not simply utilitarian objects used for defence in combat; they are also symbolic objects regularly used in ceremonies of various kinds – and ceremonies are the dramatic equivalent of stories.

The spear-thrower from Forrest River is also a storied object, with its depictions of different kinds of snakes interspersed on one side by emu tracks. It is likely that most of the other objects are too: the single snake design on the throwing stick from Forrest River; the symmetrical pair of snakes on Paddy Padoon’s shield from Sturt Creek; the snake groups on the mulga throwing stick from central Australia; the asymmetrical pair of snakes appearing on both back and front of the painted carrying dish; and the serpentine sculpture of uncertain provenance covered in abstract designs – all these look like inspired constructions based on familiarity with snake-related events, either historical or mythic in character.

How far stories characterise these objects rather than vice-versa is perhaps a moot point. It might be said that throwing sticks, spear-throwers and shields often invite serpentine imagery for no reason other than convenient congruity between iconic representation and an object’s shape. But none of the objects here appear to be merely utilitarian, with storied elements added by way of afterthought. Each snake motif is an interpretation, a ‘work of art’; and, in that sense, a boomerang or spear-thrower is no less a blank slate than an empty canvas or vacant wooden panel. As works of the imagination, all snakes here are ‘Dreamings’. That is perhaps all they have in common.